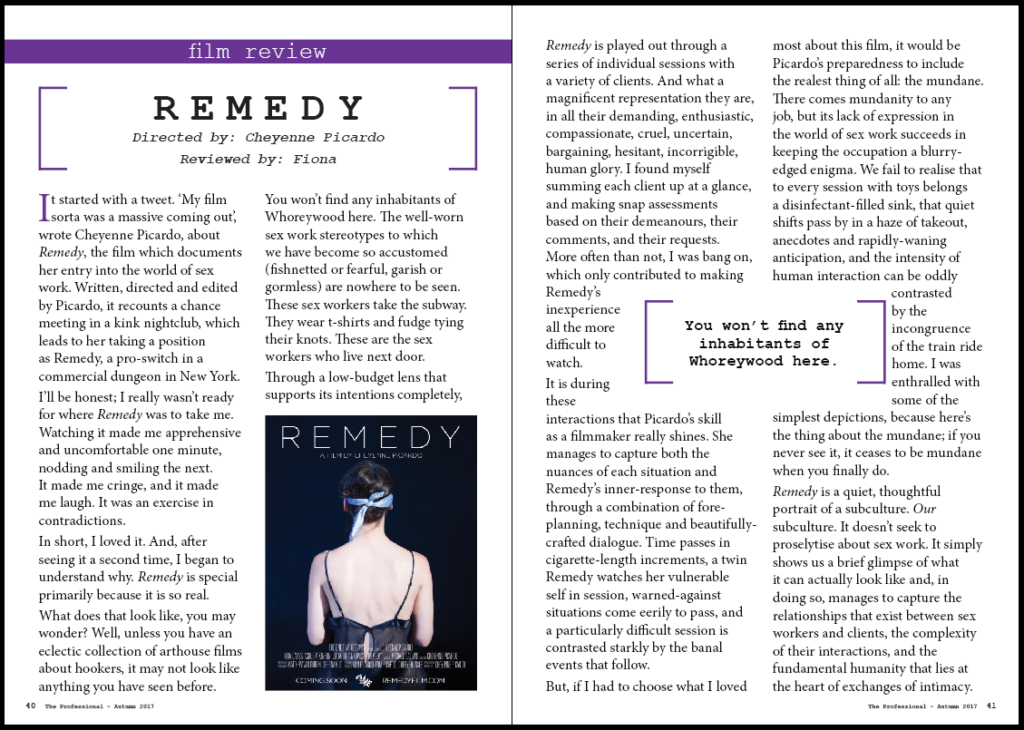

TOP GIRL & REMEDY

Sex and Economics

With Ulrich Seidl’s “IM KELLER,” Cheyenne Picardo’s “REMEDY” and Tatjana Turanskyj’s “TOP GIRL OR LA DÉFORMATION PROFESSIONELLE” there are currenty three films released in cinemas that deal with private and commercial sexual fantasies in very different ways. Seidl’s film shows BDSM people, two private and a professional couple, like exhibited objects in fairground booths, only to be seen by people with high school graduation – a kind of visual slumification in cinematic Louboutins. At least Seidl lets his protagonists talk. And especially the speech of a masochistic woman, naked and bound, about her precise differentiation between erotic submission and consensual pain opposed to violence and abuse, shows the high amount of self-reflexion that her sexual preference requires.

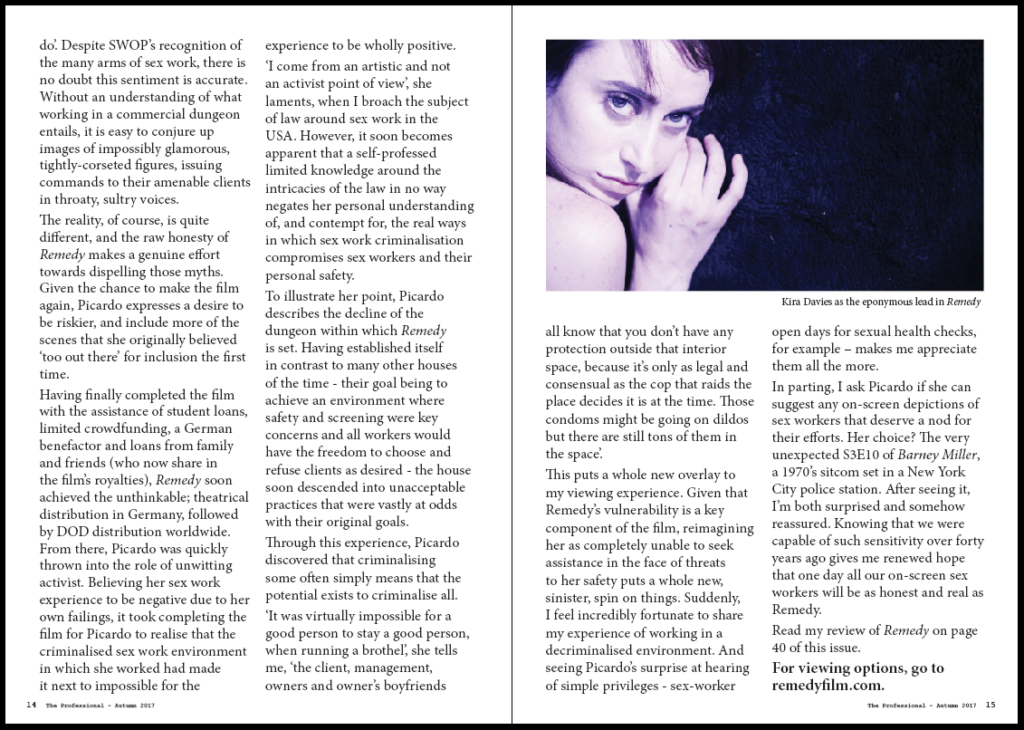

REMEDY and TOP GIRL on the other hand are about the commercial side of BDSM, but approach this subject with totally different perspectives. Cheyenne Picardo, director of REMEDY, worked in New York as a switch in a BDSM club, so she knows both the dominant and the submissive side. REMEDY is an autobiographic film about her experiences. Tatjana Turanskyj’s TOP GIRL, however, is more reminiscent of René Pollesch’s theater of discoure that was popular in the nineties. It is the second part of a planned trilogy about women and work. Even though it contains a plot about Helena, an unemployed actress (Julia Hummer) who works as an escort and fulfills the sexual desires of her clients, mostly the film is about materials, phrases and theses in an accented artificiality, often in parodic inversion. A lecture about cosmetic surgery is so much flavored with post-feministic rhetoric that only a feminist critique on self-optimisation remains. Relationships between people arise only on a material basis, it is all about money and work, with the money only being passed on concealed in envelopes. The men’s sexual fantasies are almost always about gender switching, like Judith Butler proposed it as a feminist strategy some years ago. In Turanskyj’s film, male submission fantasies are becoming fantasies again, in which men occupy a female position and move to a place from which they can fantasize about the subjugation of femininity, even if the formally assume the submissive position.

The girl is always below, down to the symbolic or real extinction. Whether TOP GIRL actually knows the world the film is about is ultimately irrelevant for the artistic concept. Economics is the cause for the disappearance of the female identity, and sex work is an intensified form of that, as it kills the body more quickly. The roles in this film describe positions, not characters. Helena and her mother represent two generations of false consciousness. The eldery because she follows an ideal of self-realization that turns out to be a market-compliant self-confinement, the younger one because she fails to recognize the relentless commodification and objectification of her body. She thinks of herself as a player in this game, but is only a screen for projection and agent of self-extinction. There are no personal, only business relationships between these two figures. It is a thesis film about which one can and should talk, but which does not have any aesthetically representative function and whose relationship to a pre-cinematic, pre-conceptual reality exists only theoretically and metaphorically.

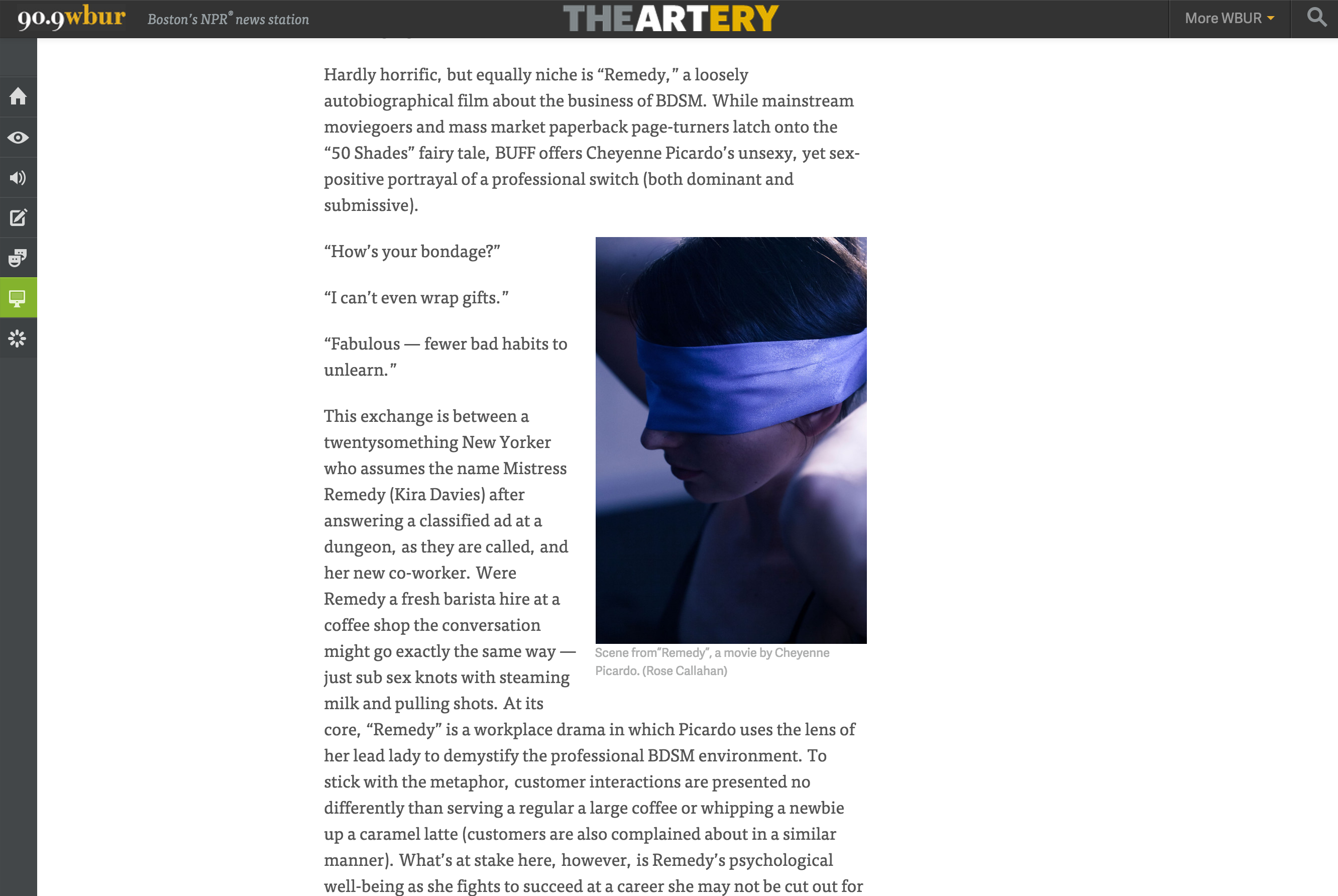

Cheyenne Picardo’s film REMEDY is the opposite of TOP GIRL: a cinematic autobiography that is particularly interested in the relationship between the sex worker Remedy and her clients and the feelings associated with that. It is not because of financial distress that Remedy begins to work as a dominatrix and later as a submissive, but only out of personal interest in the BDSM scene of New York, particularly as someone challenges her: “You could never do that!” There is no sex in the club that Remedy works in – prostitution is illegal in New York, but BDSM clubs are allowed. The problem there is not the lack of intensity in the encounters, but an excess of it. Remedy is not hurt or deformed, but her experience move her so much that she decides to quit the job. Cheyenne Picardo shows some absurd events, like Remedy’s first session as a dominatrix, where she is supposed to give a mean guy a dental treatment, but instead gets him to fall asleep by giving him a foot massage. But more important are other encounters, for example when she meets a friendly flagellant and switches roles with him, resulting in a joyful competition about who can take the most blows.

Remedy likes the phyiscal aspects of her job, but not the psychic ones. She does not offer [sessions where she receives] “extreme humiliation” and she never strips naked, but when a man lets her dance being bound in front of him, this scenes stays with her for a long time. If Remedy is humiliated or aroused in that critical moment, the film does not tell, but it is not important anyway. REMEDY tells of an excess of intensity in the BDSM sessions, something that can not be simply shut off in daily life. Remedy and her clients come very close, but this closeness turns out to be an illusion.

Picardo made the film in a very direct and improvised style, citing the films of Mike Leigh as a role model, as well as the film WORKING GIRLS (1986) by avant-gardist Lizzie Borden (not to be confused with Melanie Griffith’s film WORKING GIRL from 1988). She puts the shabbiness of the BDSM studio, where there is always a mop in the corner and some piece of bondage equipment on the edge of tipping over, in contrast to the excitingly staged interactions betweens the people. Picardo said about REMEDY: “The film should do justice to the people in the scene, professional or not. I had to show the good and the bad things, without condemning sex work or the concept of kinky sex.”

And she succeeded with this very personal film.