REVIEW in Programmkino

REMEDY tells of the emotional journey of the leading woman in a seductive low-budget indie look, that reminds a bit of cinema verité and the style of Wong Kar-Wai … but is in any case a far cry from high-gloss productions like EYES WIDE SHUT. – Programmkino

REMEDY got reviewed by Programmkino.de!

(Translation by Toby Tentakel.)

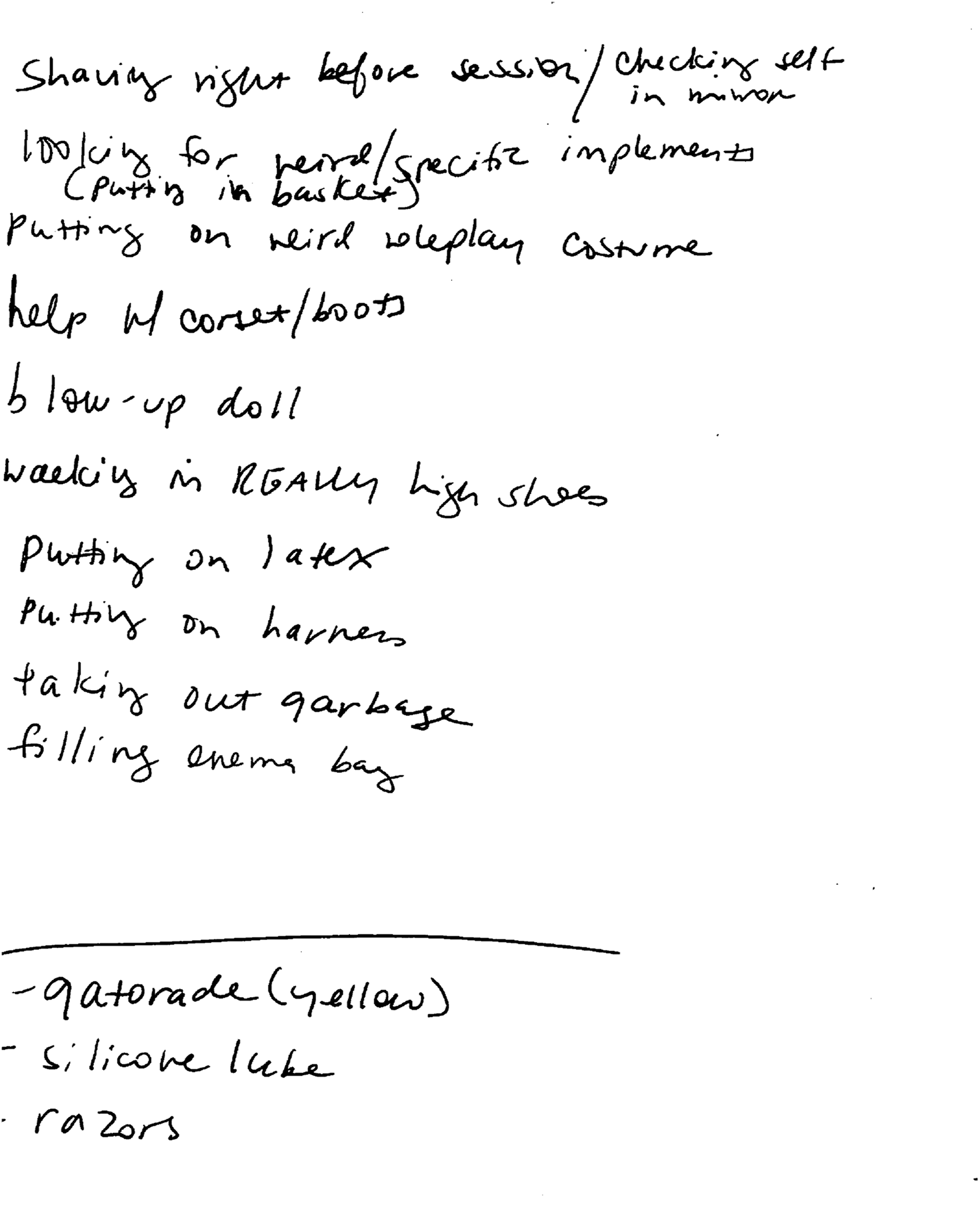

A club in New York. A young woman, her name shall remain unknown, watches a BDSM performance. “Do you know someone who does that?” She asks a friend. “That’s not for you,” he replies. This is the beginning: a challenge, a game. The woman contacts a professional BDSM studio and now calls herself Mistress Remedy. She meets her colleagues and learns the processes, equipment and No-Gos: The women don’t undress and have not – at least officially – sex with clients. Prostitution is illegal in the United States.

Based on her own experience as a professional switch (someone who can assume both the dominant and submissive role), Cheyenne Picardo tells of Remedy’s encounters and the emotions involved with them. Some scenes are quite bizarre. The very first customer wants, for example, a dental treatment with anesthetics from Remedy, but she instead puts him to sleep with a foot massage. Another loves to be used as a piece of furniture while two women smoke and talk about their relationship life. Unlike countless pseudo-documentaries on TV, REMEDY is not about showing the most shocking fantasies imaginable, but rather the interpersonal life, what is happening invisibly between Remedy and her customers. With one client, for example, she starts a contest to see who can endure the most pain, a game that appeals to Remedy. Another one teaches her professional bondage and ties her into a stylish package after he notices her lousy technique.

On the way home (one of the very few moments that take place outside the studio) you can see Remedy in the subway, dreaming. She finally decides to work as a sub, to be dominated by customers. This will get her more money, but she does not yet expect how intense and disturbing this experience will get for her.

REMEDY tells of the emotional journey of the leading woman in a seductive low-budget indie look, that reminds a bit of cinema verité and the style of Wong Kar-Wai (Picardo cites Leigh, Cronenberg and Lizzie Borden as her role models), but is in any case a far cry from high-gloss productions like EYES WIDE SHUT. In the corner of one of the sordid playrooms are buckets and a broom, a throne with a wooden cross is poorly attached to the wall and might tip over any time. This depiction does not diminish the emotional intensity of the narrated scenes at all, which is especially due to Kira Davies credible depiction of Remedy as a curious, open-minded and intelligent character who is also inexperienced and prone to overconfidence. Finally, Remedy’s self-experience experiment demands too much of her. Cheyenne Picardo stages this neither as a complete disaster, nor does she hold the BDSM scene responsible for Remedy’s collapse. REMEDY tells of how valuable, entertaining, sometimes painful but definitely interesting it is to make experiences with other people.